If you are among the new entrants to the regulated payments space you should know that, in a bit to captivate and inspire a generation, the European Banking Authority has published

the final 'regulatory technical standards' for payment user authentication and the secure communication of payments data. The standards should take effect in the second half of 2019, but the authorities are keen for regulated payment service providers (PSPs) to adopt them as soon as possible. They are written in legalese, but I've summarised them below in a bid to get them straight in my own head. Grab a coffee before proceeding!

Strong customer authentication

PSPs must know they are dealing with their own customer by applying strong customer authentication. This is subject to certain permitted exemptions outlined below. PSPs must also protect the confidentiality and the integrity of each customer's personalised security credentials. Their security measures must be documented, periodically tested, evaluated

and audited by auditors with expertise in IT security and payments and

operationally independent within or from the PSP.

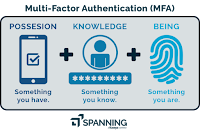

Broadly, authentication must be based on two

or more elements of 'knowledge' (password/PIN), 'possession' (card/device) and 'inherence' (fingerprint/iris scan).

These elements must be subject

to measures designed to prevent disclosure (in the case of knowledge) ,

replication (in the case of possession) and resistance against

unauthorized use of device or software (in the case of inherence).

The

breach of one element must not compromise the reliability of the others.

Certain measures must also mitigate the risk that a multi-purpose access

device has itself been compromised.

Credentials and Code

Authentication

credentials must be masked when displayed and not fully readable as

they are being entered; not stored in plaintext; and must be protected

from unauthorized disclosure.

PSPs must document how they encrypt

credentials or render them unreadable.

The creation, processing and

routing of credentials must be done in secure environments that accord

with industry standards.

Specific requirements govern the process of associating the

user with credentials; delivery; authentication of devices and software;

and the renewal, destruction, deactivation and revocation of

credentials.

Authentication

must result in the generation of an authentication code that is only

accepted once by the PSP when the payer uses it to: access the payer’s

payment account online, initiate an electronic payment transaction or to

carry out any action through 'a remote channel which may imply a risk of

payment fraud or other abuse'.

No

information on any of the authentication elements can be derived from

the disclosure of the authentication code; nor can it be possible to

generate a new authentication code based on the knowledge of any

previous code. The code must not be able to be forged.

Where

the authentication has failed to generate an authentication code, it

must not be possible to identify which of the authentication elements was

incorrect.

No

more than 5 failed authentication attempts can take place consecutively

before the authentication tool is blocked, either temporarily (based on certain

factors) or permanently (after a warning). The user has 5

minutes of inactivity after being authenticated before access must

time-out.

Dynamic linking!

The payer must be made aware of both the amount of the proposed payment transaction

and of the proposed payee. The authentication code must also be ‘dynamically linked’

(specific to) the amount and the payee. Any change to the amount or

the payee must result in the invalidation of the authentication code that was

generated.

PSPs must ensure the confidentiality, authenticity and

integrity of the amount of the transaction and the payee throughout all

of the phases of the authentication; as well as the information

displayed to the payer including the generation, transmission and use of the

authentication code.

Transaction monitoring

PSPs must monitor interaction with their customers to detect unauthorised or fraudulent payment transactions, taking into account elements which are typical of the user when normally using the credentials and, at a minimum, the following risk-based factors:

- lists of compromised or stolen authentication elements;

- the amount of each payment transaction;

- known fraud scenarios in the provision of payment services;

- signs of malware infection in any sessions of the authentication procedure; and

- where the access device or software is provided by the PSP, a log of the use of the device or software and the abnormal use of the device or software.

Exemptions from strong customer authentication

The permitted exemptions (subject to transaction monitoring, and quarterly assessments to be shared with the FCA on request) are:

- checking the balance or the last 90 days of transactions without entering sensitive payment data;

- a contactless payment of up to €50, a series of up to €150 or 5 consecutive contactless payments;

- payment at an unattended parking or transport ticket terminal;

- the payee is included in a list of trusted payees (unless adding to or changing the list);

- recurring payments (after authenticating for the first);

- transfers between the users’ own accounts with the same PSP;

- a remote electronic payment of up to €30, consecutive payments of up to €100 or 5 consecutive remove electronic payments;

- commercial payment processes or protocols where the FCA is satisfied they guarantee at least the same level of security as under PSD2;

- low risk remote electronic payment transactions (based on certain risk factors) where:

o the fraud rate is below the relevant reference rate;

o the amount is below a specific threshold; and

o the PSP’s real time risk analysis hasn’t identified certain specified problems.

Secure communcations

A PSP's communication sessions must be protected against the capture of authentication data transmitted during authentication, and against manipulation by unauthorised parties based on certain communication standards. These include secure identification of payer’s and payee’s devices; traceability of both the transactions and the interaction with the user and other participants in transactions; and a secure access interface between payer and online payment accounts.

The access interface must allow for access by the user’s chosen account information service providers (AISPs) and payment initiation service providers (PISPs), although access by AISPs and PISPs can be facilitated via a dedicated interface that meets certain requirements.

Wakey-wakey!

The End.