The second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) created the need for a regulatory technical standard (RTS) to govern communications among service providers who offer online payment accounts (ASPSPs) and third party service providers (TPPs) that offer account information services (AIS) or payment initiation services (PIS). From time to time the European Banking Authority (EBA)

issues guidance on the interpretation of the RTS in practice. The

latest guidance explains certain "obstacles" that ASPSPs must avoid creating for customers who wish to use the services of TPPs. I've summarised the guidance here to make sure I understand it generally, but

please let me know if you need advice in any a specific scenario.

ASPSPs must allow TPPs to connect to their systems through either a "dedicated interface" or the same interface that its customers use for authentication and communication. The challenge is that the dedicated interface must not create "obstacles" to the TPP's provision of payment initiation and account information services. The EBA is particularly concerned about scenarios where the customer has

to be redirected from the TPP's system to the ASPSP's system in order

to be authenticated. TPPs have argued that such redirection is an

obstacle to the customer experience in accessing their payment accounts,

where that is the only method of authenticating the customer.

The RTS itself notes some obstacles, but the EBA guidance now provides other examples in terms of:

• the types of authentication procedures that ASPSPs’ interfaces are required to support;

• whether mandatory redirection at the point-of-sale is an obstacle;

• whether multiple Strong Customer Authentications (SCA) can be required;

• whether the 90-days re-authentication requirement can be relaxed;

• the extent to which manual account input/selection is an obstacle;

• whether additional checks on customer consent can be required; and

• what additional registrations might be permissible.

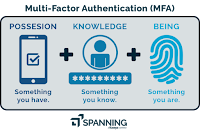

Authentication procedures that ASPSPs’ interfaces must support

If the interfaces provided by ASPSPs do not support all the authentication procedures made available by the ASPSP to its customers, this would be a breach of the RTS and an "obstacle". So, if customers use biometrics or a mobile authentication app to access their account directly with the ASPSP, then they must also be able to do so when using their payment account via a TPP. That interface should not create unnecessary friction or add unnecessary steps in the customer journey compared to the direct customer interface.

Payments at point-of-sale

It has been argued that mandatory redirection to the ASPSP's system when the customer uses a payment initiation service (PIS) offered by a payment initiation service provider (PISP) to initiate a payment at the point-of-sale is an obstacle because redirection only works in a web-browser or mobile apps-based environment. For payment initiation services to work at point-of-sale, PISPs argue that ASPSPs should be required to enable 'decoupled' or 'embedded' authentication flows, even if they don't offer that to their customers when paying directly.

The EBA says that while PSD2 does not oblige ASPSPs to enable PIS-initiated payments using authentication procedures that the ASPSP does not yet offer to its customers directly, if an ASPSP were to offer to its customers the ability to perform instant payments at the point of sale directly, then the ASPSP should also allow its customers to initiate instant payments using a PISPs’ services at the point of sale, within the same amount limits.

Requiring multiple strong customer authentications (SCA)

The authentication of the customer with the ASPSP as part of the TPP user experience using a redirection or decoupled approach would be an "obstacle" if it creates unnecessary friction or add unnecessary steps, compared to the authentication procedure offered by the ASPSP to its customers when accessing their payment accounts or initiating a payment directly.

Similarly, when a customer is using a PISP to initiate a payment, it would be an obstance if one SCA were required to access the account data, and a separate SCA for initiating the payment, unless required by the ASPSP as part of "duly justified security arguments" in a particular case (e.g. suspicion of fraud for a particular transaction) and the ASPSP could substantiate that upon request by the local regulator.

The fact that the ASPSP may require a separate SCA for ‘log-in’ (or to access payment account data more generally) when the customer directly initiates a payment with the ASPSP, is not a sufficient ground to justify applying two SCAs in the PIS scenario.

However, in some PIS journeys customers do not specify which payment account is to be debited in the payment initiation request, and only do that when transferred to the ASPSP’s domain/system. In such cases, it would not be considerd an obstacle for the ASPSP to require one SCA to access the list of payment accounts in its system, and a second SCA to authenticate the payment.

Two SCAs may also be necessary for a combined use of an account information service and a payment initiation service (unless an exemption applies): one to access the payment account data and another to initiate the payment.

90-day re-authentication for Account Information Services (AIS)

The RTS provides an exemption from the requirement to apply SCA for each access to the ASPSPs system where the AIS accesses only a limited set of data (account balance and/or 90 days of payment transactions) and its customers must re-authenticate at least every 90 days. This is to balance ease of use with increased security. The EBA "advises" local regulators to encourage all ASPSPs to use this exemption.

Account input or selection

Interfaces that require customers to manually input their IBAN into the ASPSP’s system in order to be able to use a TPP’s services are an "obstacle".

To avoid this, either:

- the TPP can seek its customer's consent to retrieve the list of all her accounts with the ASPSP via the ASPSP's interface and display it to the customer in the TPP's system, so she can select the account and the TPP can then request access or initiate a payment using the account details; or

- if the ASPSP has implemented a redirection or decoupled approach and the TPP does not extract and then transmit the account details to the ASPSP with its customers' request, the customer could select the relevant account(s) on the ASPSPs’ domain during the ASPSP's authentication procedure, in a way that is no more complicated than selecting the account(s) directly with the ASPSP (e.g. via a drop-down list of accounts, or prepopulated account details if only one).

In an "embedded" scenario, however, where the customer's credentials are exchanged between the TPP and the ASPSP and the customer does not interact with the ASPSP to authenticate, a PISP may need to obtain the details of the account from the customer in advance (if it does not also have an AIS license and/or consent from the customer to access the list of accounts). That's because a PISP is not entitled to access the list of all the customer’s payment

accounts, as this information goes beyond the scope of data that PISPs

have the right to access. So not providing the list of all payment accounts to a PISP is not an "obstacle".

However, even where the customer only selects the account on the ASPSP’s domain, the ASPSP should provide to the PISP the number of the account that was selected and from which the payment was initiated, if this information is also made available to the customer when the payment is initiated directly. Once the account number is provided to the PISP, the ASPSP should not request the customer to re-select that account when using the PISP again, because that would be an "obstacle".

Additional checks on consent

It is the regulatory obligation and the responsibility of each TPP to ensure that it has obtained the customer's explicit consent to the use of its service. The ASPSP must not make its own check for whether the customer gave that consent to the TPP, and it would be an "obstacle" for the ASPSP to require the customer to give that prior consent.

Similarly, the ASPSPs contract with its customers “should not contain any provisions that would make it more difficult, in any way, to use the payment services of other payment service providers...”. This extends to access by individual authorised users on corporate accounts.

Additional registrations

Requiring a TPP to go through additional registration processes with the ASPSP to access the ASPSP’s interface would be an obstacle, unless (a) technically required to enable a secure communication (e.g. pre-registration to use the ASPSP’s mobile banking app or a dedicated/decoupled app), (b) processed in a timely manner, and (c) does not create unnecessary friction in the customer journey.

Optional or freely agreed registrations between ASPSP and TPP are permitted (they just can't be imposed by the ASPSP).

It would also be an "obstacle" to require registration steps or processes with the ASPSP in order for the TPP to have access to the ASPSP’s production API, other than the identification of the TPP via an eIDAS certificate.